|

• soiuz.ru |

The Nightingaleby Hans Christian Andersen |

La najtingalode Hans Christian Andersen |

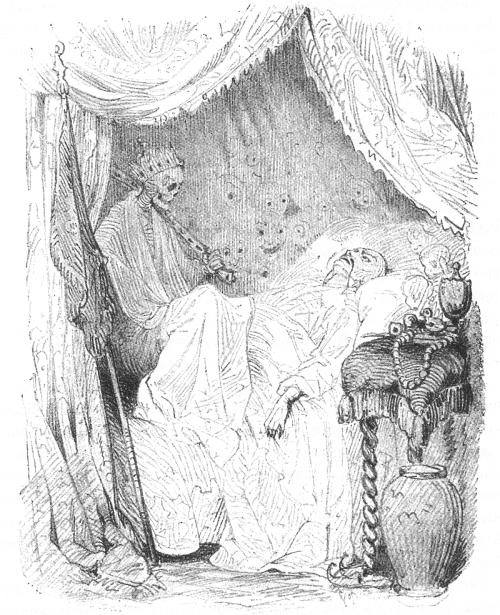

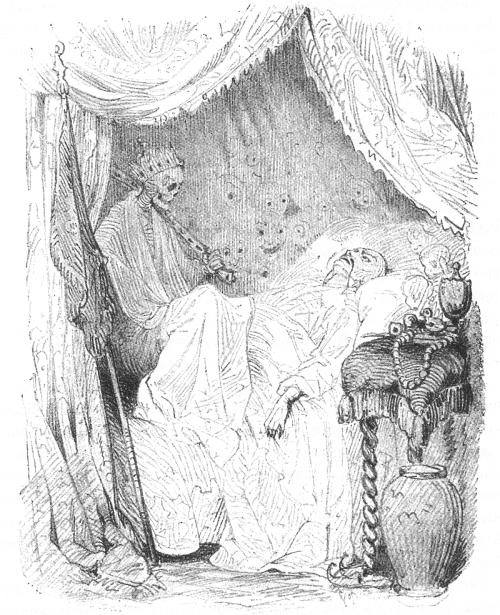

| The poor emperor, finding he

could scarcely breathe with a strange weight on his

chest, opened his eyes, and saw Death sitting there. He

had put on the emperor's golden crown, and held in one

hand his sword of state, and in the other his beautiful

banner. All around the bed and peeping through the long

velvet curtains, were a number of strange heads, some

very ugly, and others lovely and gentle-looking. These

were the emperor's good and bad deeds, which stared him

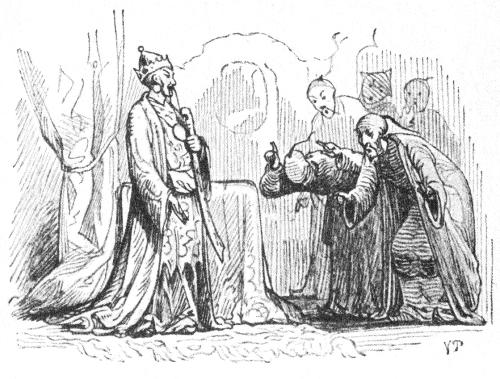

in the face now Death sat at his heart. “Do you remember this?” “Do you recollect that?” they asked one after another, thus bringing to his remembrance circumstances that made the perspiration stand on his brow. “I know nothing about it,” said the emperor. “Music! music!” he cried; “the large Chinese drum! that I may not hear what they say.” But they still went on, and Death nodded like a Chinaman to all they said. “Music! music!” shouted the emperor. “You little precious golden bird, sing, pray sing! I have given you gold and costly presents; I have even hung my golden slipper round your neck. Sing! sing!” But the bird remained silent. There was no one to wind it up, and therefore it could not sing a note. Death continued to stare at the emperor with his cold, hollow eyes, and the room was fearfully still. Suddenly there came through the open window the sound of sweet music. Outside, on the bough of a tree, sat the living nightingale. She had heard of the emperor's illness, and was therefore come to sing to him of hope and trust. And as she sung, the shadows grew paler and paler; the blood in the emperor's veins flowed more rapidly, and gave life to his weak limbs; and even Death himself listened, and said, “Go on, little nightingale, go on.” “Then will you give me the beautiful golden sword and that rich banner? and will you give me the emperor's crown?” said the bird. So Death gave up each of these treasures for a song; and the nightingale continued her singing. She sung of the quiet churchyard, where the white roses grow, where the elder-tree wafts its perfume on the breeze, and the fresh, sweet grass is moistened by the mourners' tears. Then Death longed to go and see his garden, and floated out through the window in the form of a cold, white mist. “Thanks, thanks, you heavenly little bird. I know you well. I banished you from my kingdom once, and yet you have charmed away the evil faces from my bed, and banished Death from my heart, with your sweet song. How can I reward you?” “You have already rewarded me,” said the nightingale. “I shall never forget that I drew tears from your eyes the first time I sang to you. These are the jewels that rejoice a singer's heart. But now sleep, and grow strong and well again. I will sing to you again.” And as she sung, the emperor fell into a sweet sleep; and how mild and refreshing that slumber was! When he awoke, strengthened and restored, the sun shone brightly through the window; but not one of his servants had returned– they all believed he was dead; only the nightingale still sat beside him, and sang. “You must always remain with me,” said the emperor. “You shall sing only when it pleases you; and I will break the artificial bird into a thousand pieces.” “No; do not do that,” replied the nightingale; “the bird did very well as long as it could. Keep it here still. I cannot live in the palace, and build my nest; but let me come when I like. I will sit on a bough outside your window, in the evening, and sing to you, so that you may be happy, and have thoughts full of joy. I will sing to you of those who are happy, and those who suffer; of the good and the evil, who are hidden around you. The little singing bird flies far from you and your court to the home of the fisherman and the peasant's cot. I love your heart better than your crown; and yet something holy lingers round that also. I will come, I will sing to you; but you must promise me one thing.” “Everything,” said the emperor, who, having dressed himself in his imperial robes, stood with the hand that held the heavy golden sword pressed to his heart. “I only ask one thing,” she replied; “let no one know that you have a little bird who tells you everything. It will be best to conceal it.” So saying, the nightingale flew away. The servants now came in to look after the dead emperor; when, lo! there he stood, and, to their astonishment, said, “Good morning.” |

La malfelicha

imperiestro apenau povis spiri; estis al li, kvazau io

kushus sur lia brusto. Li malfermis la okulojn, kaj tiam

li vidis, ke tio, kio sidis sur lia brusto, estas la

morto. Ghi metis sur sin lian oran kronon kaj tenis en

unu mano la oran glavon de la imperiestro kaj en la dua

mano lian belegan standardon. El la faldoj de la grandaj

veluraj kurtenoj chirkaue rigardis strangaj kapoj, el

kiuj kelkaj estis tre malbelaj, aliaj estis pacplenaj kaj

mildaj. Tio estis chiuj malbonaj kaj bonaj faroj de la

imperiestro, kiuj nun, kiam la morto sidis sur lia koro,

staris antau liaj okuloj. “Chu vi memoras chi tion?” murmuretis unu post alia. “Chu vi memoras chi tion?” Kaj ili rakontis al li tiom multe, ke la shvito fluis de lia frunto. “Tion mi neniam sciis,” ghemis la imperiestro. Al li farighis tiel malfacile, tiel timige, ke li ekkriis: - Muzikon! Muzikon chi tien! Batu en grandan hhinan tamburon! Mi ne volas vidi kaj audi ilin! Sed la timigaj vochoj ne chesis, kaj la morto, kvazau malnova hhino, balancis la kapon che chiu ilia vorto. - Muzikon chi tien, muzikon! - ankorau pli laute ekkriis la imperiestro. - “Vi, charma ora birdeto, kantu do, kantu! Mi donis al vi oron kaj juvelojn, mi ech pendigis chirkau via kolo mian oran pantoflon, kantu do, kantu!” Sed la birdo silentis, char estis neniu, por ghin strechtordi, kaj sen tio ghi ne kantis. Sed la morto daurigis rigardi lin per siaj grandaj malplenaj okulkavoj, kaj chirkaue estis tiel silente, tiel terure silente. Sed jen subite, ghuste apud la fenestro, eksonis plej bela kantado. Ghi venis de la malgranda viva najtingalo, kiu sidis ekstere sur brancho. Ghi audis pri la mizero de sia imperiestro, kaj tial ghi venis por kanti al li konsolon kaj esperon. Kaj dum ghi kantis, la fantomoj pli kaj pli palighis, chiam pli rapide pulsis la sango en la malforta korpo de la imperiestro, kaj ech la morto mem auskultis kaj diris: “Daurigu, najtingaleto, daurigu!” “Jes, se vi donos al mi la belegan oran glavon, se vi donos al mi la richan standardon kaj la kronon de la imperiestro!” Kaj la morto donis chiujn multekostajhojn, po unu por chiu kanto kaj la najtingalo estis senlaca en sia kantado. Ghi kantis pri la silenta tombejo, kie kreskas la blankaj rozoj, kie odoras la siringo, kaj kie la fresha herbo estas malsekigata de la larmoj de la postvivantoj. Tiam la morto eksopiris pri sia ghardeno, kaj kiel malvarma blanka nebulo ghi elflugis tra la fenestro. “Mi dankas, mi dankas!” diris la imperiestro; “vi, chiela birdeto, mi bone vin konas! Vin mi ekzilis el mia lando kaj regno, kaj tamen vi forkantis de mia lito la malbonojn, vi forpelis la morton de mia koro! Kiel mi povas vin rekompenci?” “Vi min rekompencis!” diris la najtingalo; “larmojn elvershis viaj okuloj, kiam mi la unuan fojon kantis antau vi; tion mi neniam forgesos al vi, tio estas la juveloj, kiuj estas agrablaj al la koro de kantanto. Sed dormu nun, farigu fresha kaj sana! Mi kantos kaj endormigos vin.” Ghi kantis; kaj la imperiestro dolche endormighis; kvieta kaj bonfara estis la dormo. La radioj de la suno tra la fenestro falis sur lin, kiam li, refortigita kaj sana, vekighis. Ankorau neniu el liaj servistoj revenis, char ili pensis, ke li jam ne vivas, sed la najtingalo ankorau tie sidis kaj kantis. “Por chiam vi devas resti che mi!” diris la imperiestro; “vi kantos nur tiam, kiam vi volos, kaj la artefaritan birdon mi disbatos je mil pecoj.” “Ne faru chi tion!” diris la najtingalo; “la bonon, kiun ghi povis fari, ghi ja faris; konservu ghin, kiel antaue! Mi ne povas loghi en kastelo, sed permesu al mi venadi, kiam mi mem havos la deziron. Tiam mi vespere sidos tie sur la brancho apud la fenestro, kaj mi kantos al vi, por ke vi farighu gaja, sed samtempe ankau meditema. Mi kantos pri la felichuloj kaj pri tiuj, kiuj suferas; mi kantos pri la bono kaj malbono kiu estas kashata antau vi. La malgranda birdeto flugas malproksime, al la malricha fiskaptisto, al la tegmento de la kampulo, al chiu, kiu estas malproksima de vi kaj de via kortego. Vian koron mi amas pli ol vian kronon, kaj tamen la krono havas en si ion de la odoro de sankteco. Mi venados, mi, kantados al vi! Sed unu aferon vi devas promesi al mi!” “Chion!” diris la imperiestro, kaj li staris en siaj imperiestraj vestoj, kiujn li mem surmetis sur sin, kaj la glavon, kiu estis peza de oro, li almetis al sia koro. “Pri unu afero mi vin petas! Rakontu al neniu, ke vi havas birdeton, kiu chion diras al vi, tiam chio iros ankorau pli bone!” Kaj la najtingalo forflugis. La servistoj envenis, por rigardi la mortintan imperiestron.... Surprizite ili haltis, kaj la imperiestro diris al ili: “Bonan tagon!” |

Бедный император едва дышал, ему казалось, что кто-то сжимает его горло. Он приоткрыл глаза и увидел, что на груди у него сидит Смерть. Она надела себе на голову корону императора, в одной руке у нее была его золотая сабля, а в другой - императорское знамя. А кругом из всех складок бархатного балдахина выглядывали какие-то страшные рожи: одни безобразные и злые, другие - красивые и добрые. Но злых было гораздо больше. Это были злые и добрые дела императора. Они смотрели на него и наперебой шептали.

- Помнишь ли ты это? - слышалось с одной стороны.

- А это помнишь? - доносилось с другой. И они рассказывали ему такое, что холодный пот выступал у императора на лбу.

- Я забыл об этом, - бормотал он. - А этого никогда и не знал...

Ему стало так тяжело, так страшно, что он закричал:

- Музыку сюда, музыку! Бейте в большой китайский барабан! Я не хочу видеть и слышать их!

Но страшные голоса не умолкали, а Смерть, словно старый китаец, кивала при каждом их слове,

- Музыку сюда, музыку! - еще громче вскричал император. - Пой хоть ты, моя славная золотая птичка! Я одарил тебя драгоценностями, я повесил тебе на шею золотую туфлю!.. Пой же, пой!

Но птица молчала: некому было завести ее, а без этого она петь не умела.

Смерть, усмехаясь, глядела на императора своими пустыми глазными впадинами. Мертвая тишина стояла в покоях императора.

И вдруг за окном раздалось чудное пение. То был маленький живой соловей. Он узнал, что император болен, и прилетел, чтобы утешить и ободрить его. Он сидел на ветке и пел, и страшные призраки, обступившие императора, все бледнели и бледнели, а кровь все быстрее, все жарче приливала к сердцу императора.

Сама Смерть заслушалась соловья и лишь тихо повторяла:

- Пой, соловушка! Пой еще!

- А ты отдашь мне за это драгоценную саблю? И знамя? И корону? - спрашивал соловей.

Смерть кивала головой и отдавала одно сокровище за другим, а соловей всё пел и пел. Вот он запел песню о тихом кладбище, где цветет бузина, благоухают белые розы и в свежей траве на могилах блестят слезы живых, оплакивающих своих близких. Тут Смерти так захотелось вернуться к себе домой, на тихое кладбище, что она закуталась в белый холодный туман и вылетела в окно.

- Спасибо тебе, милая птичка! - сказал император. - Я узнаю тебя. Когда-то я прогнал тебя из моего государства, а теперь ты своей песней отогнала от моей постели Смерть! Чем мне вознаградить тебя?

- Ты уже наградил меня, - сказал соловей. - Я видел слезы на твоих глазах, когда первый раз пел перед тобой, - этого я не забуду никогда. Искренние слезы восторга - самая драгоценная награда певцу!

И он запел опять, а император заснул здоровым, крепким сном.

А когда он проснулся, в окно уже ярко светило солнце. Никто из придворных и слуг даже не заглядывал к императору. Все думали, что он умер. Один соловей не покидал больного. Он сидел за окном и пел еще лучше, чем всегда.

- Останься у меня! - просил император. - Ты будешь петь только тогда, когда сам захочешь. А искусственную птицу я разобью.

- Не надо! - сказал соловей. - Она служила тебе, как могла. Оставь ее у себя. Я не могу жить во дворце. Я буду прилетать к тебе, когда сам захочу, и буду петь о счастливых и несчастных, о добре и зле, обо всем, что делается вокруг тебя и чего ты не знаешь. Маленькая певчая птичка летает повсюду - залетает и под крышу бедной крестьянской хижины, и в рыбачий домик, которые стоят так далеко от твоего дворца. Я буду прилетать и петь тебе! Но обещай мне...

- Всё, что хочешь! - воскликнул император и встал с постели.

Он успел уже надеть свое императорское одеяние и прижимал к сердцу тяжелую золотую саблю.

- Обещай мне не говорить никому, что у тебя есть маленькая птичка, которая рассказывает тебе обо всем большом мире. Так дело пойдет лучше.

И соловей улетел.

Тут вошли придворные, они собрались поглядеть на умершего императора, да так и застыли на пороге.

А император сказал им:

- Здравствуйте! С добрым утром!