The Ugly Ducklingby Hans Christian Andersen |

Malbela anasidode Hans Christian Andersen |

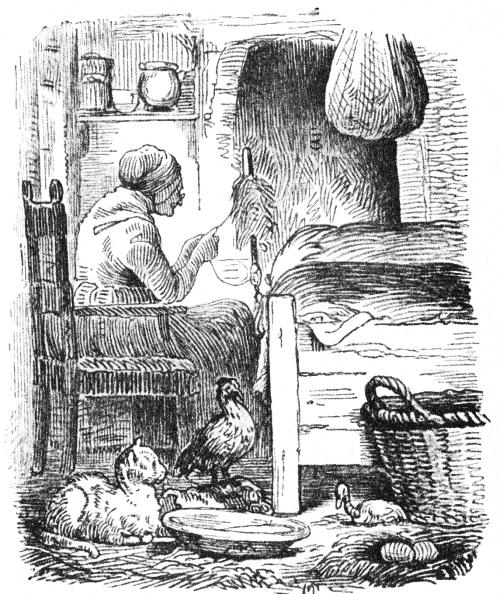

| A woman, a tom cat, and a hen

lived in this cottage. The tom cat, whom the mistress

called, “My little son,” was a great favorite; he

could raise his back, and purr, and could even throw out

sparks from his fur if it were stroked the wrong way. The

hen had very short legs, so she was called “Chickie

short legs.” She laid good eggs, and her mistress loved

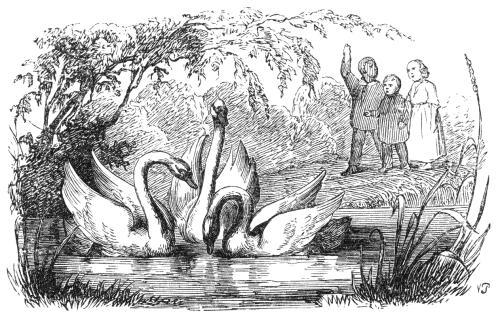

her as if she had been her own child. In the morning, the strange visitor was discovered, and the tom cat began to purr, and the hen to cluck. “What is that noise about?” said the old woman, looking round the room, but her sight was not very good; therefore, when she saw the duckling she thought it must be a fat duck, that had strayed from home. “Oh what a prize!” she exclaimed, “I hope it is not a drake, for then I shall have some duck's eggs. I must wait and see.” So the duckling was allowed to remain on trial for three weeks, but there were no eggs. Now the tom cat was the master of the house, and the hen was mistress, and they always said, “We and the world,” for they believed themselves to be half the world, and the better half too. The duckling thought that others might hold a different opinion on the subject, but the hen would not listen to such doubts. “Can you lay eggs?” she asked. “No.” “Then have the goodness to hold your tongue.” “Can you raise your back, or purr, or throw out sparks?” said the tom cat. “No.” “Then you have no right to express an opinion when sensible people are speaking.” So the duckling sat in a corner, feeling very low spirited, till the sunshine and the fresh air came into the room through the open door, and then he began to feel such a great longing for a swim on the water, that he could not help telling the hen. “What an absurd idea,” said the hen. “You have nothing else to do, therefore you have foolish fancies. If you could purr or lay eggs, they would pass away.” “But it is so delightful to swim about on the water,” said the duckling, “and so refreshing to feel it close over your head, while you dive down to the bottom.” “Delightful, indeed!” said the hen, “why you must be crazy! Ask the cat, he is the cleverest animal I know, ask him how he would like to swim about on the water, or to dive under it, for I will not speak of my own opinion; ask our mistress, the old woman– there is no one in the world more clever than she is. Do you think she would like to swim, or to let the water close over her head?” “You don't understand me,” said the duckling. “We don't understand you? Who can understand you, I wonder? Do you consider yourself more clever than the cat, or the old woman? I will say nothing of myself. Don't imagine such nonsense, child, and thank your good fortune that you have been received here. Are you not in a warm room, and in society from which you may learn something. But you are a chatterer, and your company is not very agreeable. Believe me, I speak only for your own good. I may tell you unpleasant truths, but that is a proof of my friendship. I advise you, therefore, to lay eggs, and learn to purr as quickly as possible.” “I believe I must go out into the world again,” said the duckling. “Yes, do,” said the hen. So the duckling left the cottage, and soon found water on which it could swim and dive, but was avoided by all other animals, because of its ugly appearance. Autumn came, and the leaves in the forest turned to orange and gold. Then, as winter approached, the wind caught them as they fell and whirled them in the cold air. The clouds, heavy with hail and snow-flakes, hung low in the sky, and the raven stood on the ferns crying, “Croak, croak.” It made one shiver with cold to look at him. All this was very sad for the poor little duckling. One evening, just as the sun set amid radiant clouds, there came a large flock of beautiful birds out of the bushes. The duckling had never seen any like them before. They were swans, and they curved their graceful necks, while their soft plumage shown with dazzling whiteness. They uttered a singular cry, as they spread their glorious wings and flew away from those cold regions to warmer countries across the sea. As they mounted higher and higher in the air, the ugly little duckling felt quite a strange sensation as he watched them. He whirled himself in the water like a wheel, stretched out his neck towards them, and uttered a cry so strange that it frightened himself. Could he ever forget those beautiful, happy birds; and when at last they were out of his sight, he dived under the water, and rose again almost beside himself with excitement. He knew not the names of these birds, nor where they had flown, but he felt towards them as he had never felt for any other bird in the world. He was not envious of these beautiful creatures, but wished to be as lovely as they. Poor ugly creature, how gladly he would have lived even with the ducks had they only given him encouragement. The winter grew colder and colder; he was obliged to swim about on the water to keep it from freezing, but every night the space on which he swam became smaller and smaller. At length it froze so hard that the ice in the water crackled as he moved, and the duckling had to paddle with his legs as well as he could, to keep the space from closing up. He became exhausted at last, and lay still and helpless, frozen fast in the ice. Early in the morning, a peasant, who was passing by, saw what had happened. He broke the ice in pieces with his wooden shoe, and carried the duckling home to his wife. The warmth revived the poor little creature; but when the children wanted to play with him, the duckling thought they would do him some harm; so he started up in terror, fluttered into the milk-pan, and splashed the milk about the room. Then the woman clapped her hands, which frightened him still more. He flew first into the butter-cask, then into the meal-tub, and out again. What a condition he was in! The woman screamed, and struck at him with the tongs; the children laughed and screamed, and tumbled over each other, in their efforts to catch him; but luckily he escaped. The door stood open; the poor creature could just manage to slip out among the bushes, and lie down quite exhausted in the newly fallen snow. It would be very sad, were I to relate all the misery and privations which the poor little duckling endured during the hard winter; but when it had passed, he found himself lying one morning in a moor, amongst the rushes. He felt the warm sun shining, and heard the lark singing, and saw that all around was beautiful spring. Then the young bird felt that his wings were strong, as he flapped them against his sides, and rose high into the air. They bore him onwards, until he found himself in a large garden, before he well knew how it had happened. The apple-trees were in full blossom, and the fragrant elders bent their long green branches down to the stream which wound round a smooth lawn. Everything looked beautiful, in the freshness of early spring. From a thicket close by came three beautiful white swans, rustling their feathers, and swimming lightly over the smooth water. The duckling remembered the lovely birds, and felt more strangely unhappy than ever. “I will fly to those royal birds,” he exclaimed, “and they will kill me, because I am so ugly, and dare to approach them; but it does not matter: better be killed by them than pecked by the ducks, beaten by the hens, pushed about by the maiden who feeds the poultry, or starved with hunger in the winter.” Then he flew to the water, and swam towards the beautiful swans. The moment they espied the stranger, they rushed to meet him with outstretched wings. “Kill me,” said the poor bird; and he bent his head down to the surface of the water, and awaited death. But what did he see in the clear stream below? His own image; no longer a dark, gray bird, ugly and disagreeable to look at, but a graceful and beautiful swan. To be born in a duck's nest, in a farmyard, is of no consequence to a bird, if it is hatched from a swan's egg. He now felt glad at having suffered sorrow and trouble, because it enabled him to enjoy so much better all the pleasure and happiness around him; for the great swans swam round the new-comer, and stroked his neck with their beaks, as a welcome. Into the garden presently came some little children, and threw bread and cake into the water. “See,” cried the youngest, “there is a new one;” and the rest were delighted, and ran to their father and mother, dancing and clapping their hands, and shouting joyously, “There is another swan come; a new one has arrived.” Then they threw more bread and cake into the water, and said, “The new one is the most beautiful of all; he is so young and pretty.” And the old swans bowed their heads before him. Then he felt quite ashamed, and hid his head under his wing; for he did not know what to do, he was so happy, and yet not at all proud. He had been persecuted and despised for his ugliness, and now he heard them say he was the most beautiful of all the birds. Even the elder-tree bent down its bows into the water before him, and the sun shone warm and bright. Then he rustled his feathers, curved his slender neck, and cried joyfully, from the depths of his heart, “I never dreamed of such happiness as this, while I was an ugly duckling.” |

Tie loghis maljuna

virino kun sia kato kaj kun sia kokino; la kato, kiun shi

nomis fileto, povosciis ghibighi kaj shđini. Ech

fajrerojn oni povis aperigi che ghi, kiam en mallumo

oni frotetis ghin kontrau la haroj. La kokino havis tre

malgrandajn malaltajn piedojn kaj tial estis nomata

piedetulino. Ghi metadis orajn ovojn, kaj la virino ghin

amis kiel sian propran infanon. Matene oni tuj rimarkis la fremdan anasidon, kaj la kato komencis shpini kaj la kokino kluki. “Kio tio estas!” ekkriis la virino kaj ekrigardis; sed char shi ne bone vidis, shi pensis pri la anasido, ke tio estas grasa anasino. “Tio estas originala kaptajho!” shi diris; “nun mi povas ricevadi anasajn ovojn. Se ghi nur ne estas anaso virseksa! Tion ni devas elprovi.” Shi prenis la anasidon prove por la dauro de tri semajnoj, sed ovoj ne aperis. La kato estis sinjoro en la domo kaj la kokino estis sinjorino, kaj ili chiam diradis: “Ni kaj la mondo”, char ili pensis, ke ili prezentas duonon, kaj ghuste la pli bonan. Al la anasido shajnis, ke oni povas havi ankau alian opinion, sed la kokino tion ne toleris. “Chu vi povoscias meti ovojn?” shi demandis. “Ne!” “Nu, en tia okazo ne malfermu la bushon!” Kaj la kato diris: “Chu vi povoscias ghibighi, chu vi povoscias shpini, chu vi povoscias aperigi fajrerojn?” “Ne!” “En tia okazo vi ne devas havi opinion, kiam saghuloj parolas!” Kaj la anasido sidis en angulo kaj estis en malbona humoro. Tiam ghi pretervole ekpensis pri la fresha aero kaj la lumo de la suno, kaj ghi ricevis tiel fortan deziron naghi sur la akvo, ke ghi fine plu ne povis sin deteni kaj konfidis tion al la kokino. “Kion vi diras?” demandis la kokino. “Vi havas nenian laboron, tial vin turmentas tiaj strangaj kapricoj. Metu ovojn au shpinu, tiam la kapricoj pasos.” “Sed estas charmege naghi sur la akvo!” respondis la anasido, “estas charmege refreshigi al si la kapon en la ondoj au subakvighi sur la fundon!” “Jes, tio kredeble estas vere bela plezuro!” diris moke la kokino; “chu vi frenezighis? Demandu do la katon, ghi estas la plej sagha estajho, kiun mi konas, chu ghi trovas tion tiel agrabla naghi sur la akvo au subakvighi! Pri mi mem mi jam ne parolas. Demandu ech nian estrinon, la maljunan virinon, pli sagha ol shi en la mondo ekzistas neniu. Chu vi pensas, ke shi volus naghi au lasi, ke la akvo fermighu super shi?” “Vi min ne komprenas!” , diris la anasido. “Se ni vin ne komprenas, kiu do povus vin kompreni? Vi ja ne pretendos, ke vi estas pli sagha ol la kato kaj la virino, ne parolante pri mi. Ne afektu, infano; kaj ne enmetu al vi frenezajhojn en la kapon! Danku vian Kreinton pro la chio bona, kion oni faris al vi! Chu oni ne akceptis vin en varman chambron kaj en societon, de kiu vi povas ion lerni? Sed vi estas sensenculo, kaj tute ne estas agrable havi kompanion kun vi! Al mi vi povas kredi, char mi deziras al vi bonon, mi diras al vi la neagrablan veron, kaj per tio oni povas ekkoni siajn verajn amikojn. Nun vi devas nur peni, ke vi lernu meti ovojn kaj shpini kaj aperigi fajrerojn!” “Mi pensas, ke mi iros en la malproksiman mondon!” diris la anasido. “Jes, faru tion!” respondis la kokino. Kaj la anasido foriris, ghi naghis sur la akvo; ghi subakvighadis, sed pro sia malbeleco ghi estis ignorata de chiuj bestoj. Jen venis autuno; la folioj en la arbaro farighis flavaj, kaj brunaj, la vento ilin forportis kaj turnopelis, kaj supre en la aero la malvarmo farighis sentebla. La nuboj estis pezaj de hajlo kaj negho, kaj sur la barilo staris korvo kaj pro malvarmo kriadis: “Au, au!” Jes, oni povis jam senti froston ech kiam oni nur pensis pri tio. Al la kompatinda anasido estis tute ne bone. Unu vesperon, kiam la suno jhus subiris mirinde bele, el inter la arbetajhoj elvenis tuta svarmo da belegaj grandaj birdoj, kiajn la anasido neniam ankorau vidis antaue, Ili estis blindige blankaj kaj havis longajn fleksighemajn kolojn; tio estis cignoj. Ili eligis strangan sonon, etendis siajn belegajn grandajn flugilojn kaj flugis el la malvarmaj regionoj al la varmaj landoj, al liberaj maroj. Ili levighis tiel alten, tiel alten, ke stranga sento ekregis en la koro de la malbela anasido. Ghi turnadis sin en la akvo kiel rado, etendis la kolon alten al ili kaj eligis tiel strangan kaj lautan krion, ke ghi ektimis mem. Ghi ne povis forgesi la belegajn, felichajn birdojn, kaj kiam ghi ilin plu ne vidis, ghi subakvighis gis la fundo, kaj, levighinte denove, ghi farighis duonfreneza. Ghi ne sciis, kiel tiuj birdoj estas nomataj, nek kien ili flugas, sed ghi amis ilin tiel, kiel ghi neniam antaue iun amis. Tamen envio ne venis en ghian koron. Kiel ech povus veni al ghi en la kapon deziri por si tian belecon! Ghi estus jam ghoja, se nur la anasoj volus ghin toleri inter si; la kompatinda malbela besto! La vintro farighis tiel malvarma, tiel malvarma! La anasido devis senlace naghadi, por malhelpi la glaciighon. Sed kun chiu nokto la truo, en kiu ghi naghadis, farighis pli kaj pli malvasta. Estis tia malvarmo, ke la glacia kovro krakis. La anasido devis senchese uzadi siajn piedojn, por ke la truo ne fermighu tute. Fine ghi lacighis, kushis tute senmove kaj tiel enfrostighis fortike en la glacion. Frue en la sekvanta mateno venis vilaghano, kiu ekvidis la kompatindan beston. Li iris, disbatis la glacion per sia ligna shuo, savis la anasidon kaj portis ghin hejmen al sia edzino. Tie ghi denove vivighis. La infanoj volis ludi kun ghi. Sed char la anasido pensis, ke ili volas fari al ghi ian doloron, ghi en sia timego enflugis ghuste en pladon kun lakto, tiel ke la lakto shprucis chirkauen en la chambron. La mastrino kun teruro interfrapis la manojn. Poste la anasido flugis sur la stablon, sur kiu staris la butero, kaj de tie en la barelon kun la faruno, kaj poste denove supren. Vi povas prezenti al vi, kiel ghi tiam aspektis! La mastrino kriis kaj penis frapi ghin per la fajroprenilo, la infanoj kuris tumulte, ridis kaj bruis. Estis bone, ke la pordo estis nefermita; tial la anasido povis tra inter la arbetajhoj savi sin en la freshe falintan neghon, kaj tie ghi kushis morte lacigita. Estus vere malgaja afero, se ni volus rakonti la tutan mizeron kaj suferojn, kiujn la anasido devis elteni dum la kruela vintro. Ghi kushis inter la kanoj en la marcho, kiam la suno denove komencis varme lumi; la alaudoj kantis, estis belega printempo. Tiam subite disvolvighis ghiaj flugiloj, ili movighis pli forte ol antaue kaj portis ghin vigle antauen; kaj antau ol ghi tion konsciis, ghi trovighis en granda ghardeno, kie la pomarboj staris tute kovritaj de florajho, kie la siringarbetoj odoris kaj klinis siajn longajn verdajn branchojn al la kviete serpentumantaj riveretoj kaj kanaloj. Ho, kiel charmege, kiel printempe freshe estis chi tie! Kaj ghuste antau ghi el la densejo elnaghis tri belaj blankaj cignoj; kun krispa plumaro ili malpeze kaj majeste glitadis sur la akvo. La anasido rekonis la belajn bestojn, kaj stranga melankolio ghin atakis. “Mi flugos al ili, al la reghaj birdoj, kaj ili mordmortigos min pro tio, ke mi, kiu estas tiel malbela, kuraghas alproksimighi al ili. Sed tiel estu! Mi preferas esti mortigita de ili, ol esti pinchata de la anasoj, pikata de la kokinoj, pushata de la servistino, kaj dum la vintro suferi chiaspecajn turmentojn!” Kaj ghi flugis sur la akvon kaj eknaghis renkonte al la belegaj cignoj, kiuj jhetis sin kontrau ghin kun disstarigitaj plumoj. “Mortigu min!” diris la kompatinda besto kaj klinis sian kapon al la spegulo de la akvo, atendante la morton. Sed kion ghi vidis en la klara akvo? Ghi vidis sub si sian propran bildon, sed tio ne estis plu mallerta, nigre-griza birdo, malbela kaj vekanta abomenon, – tio estis ankau cigno. Ne estas grave, ke oni naskighis en anasejo, se oni nur kushis en ovo de cigno! Nun ghi sentis sin plensence felicha pro la tuta mizero kaj suferoj, kiujn ghi trasurportis. Nur nun ghi komprenis sian felichon, nur nun ghi povosciis ghuste taksi la belecon, kiu salutis ghin de ciuj flankoj. Kaj la grandaj cignoj chirkaunaghis ghin kaj karesis ghin per sia beko. Tiam kelke da malgrandaj infanoj eniris en la ghardenon. Ili jhetis panon kaj grenon en la akvon, kaj la plej malgranda ekkriis: “Jen estas nova!” Kaj la aliaj infanoj ankau ekkriis ghoje: “Jes, alvenis nova!” Ili plaudis per la manoj, saltis kaj dancis, alvokis la patron kaj la patrinon, oni jhetis panon kaj kukon en la akvon, kaj ili chiuj diris: “La nova estas la plej bela, tiel juna, kaj maljunaj cignoj klinis sin antau ghi.” Tiam ghi farigis timema kaj hontema kaj kashis la kapon sub la flugiloj; en la koro estis al ghi tiel strange, ghi preskau mem ne sciis kiel. Ghi estis tre felica, sed tute ne fiera, char bona koro neniam farighas fiera. Ghi pensis pri tio, kiel ghi estis mokata kaj persekutata, kaj nun ghi audis, kiel chiuj diras, ke ghi estas la plej bela el chiuj belaj birdoj. La siringarbetoj klinis sin kun siaj branchoj al ghi en la akvon, kaj la suno lumis varme kaj freshige. Tiam ghi elrektigis sian plumaron, ghia gracia kolo levighis, kaj el la tuta koro ghi ekkriis: “Pri tiom da felicho mi ech ne songhis, kiam mi estis ankorau la malbela anasido!” |

Ňű,