The Ugly Ducklingby Hans Christian Andersen |

Malbela anasidode Hans Christian Andersen |

| It was lovely summer weather in

the country, and the golden corn, the green oats, and the

haystacks piled up in the meadows looked beautiful. The

stork walking about on his long red legs chattered in the

Egyptian language, which he had learnt from his mother.

The corn-fields and meadows were surrounded by large

forests, in the midst of which were deep pools. It was,

indeed, delightful to walk about in the country. In a

sunny spot stood a pleasant old farm-house close by a

deep river, and from the house down to the water side

grew great burdock leaves, so high, that under the

tallest of them a little child could stand upright. The

spot was as wild as the centre of a thick wood. In this

snug retreat sat a duck on her nest, watching for her

young brood to hatch; she was beginning to get tired of

her task, for the little ones were a long time coming out

of their shells, and she seldom had any visitors. The

other ducks liked much better to swim about in the river

than to climb the slippery banks, and sit under a burdock

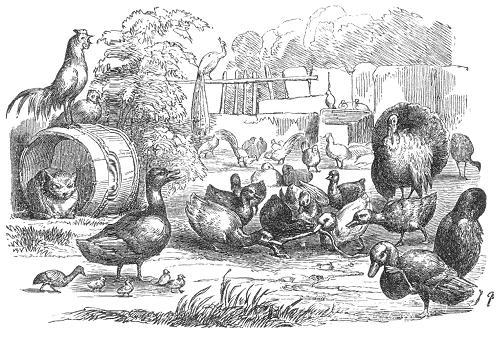

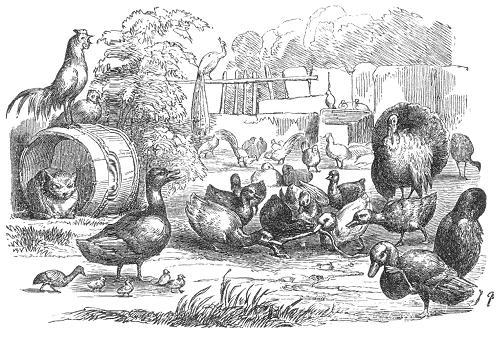

leaf, to have a gossip with her. At length one shell cracked, and then another, and from each egg came a living creature that lifted its head and cried, “Peep, peep.” “Quack, quack,” said the mother, and then they all quacked as well as they could, and looked about them on every side at the large green leaves. Their mother allowed them to look as much as they liked, because green is good for the eyes. “How large the world is,” said the young ducks, when they found how much more room they now had than while they were inside the egg-shell. “Do you imagine this is the whole world?” asked the mother; “Wait till you have seen the garden; it stretches far beyond that to the parson's field, but I have never ventured to such a distance. Are you all out?” she continued, rising; “No, I declare, the largest egg lies there still. I wonder how long this is to last, I am quite tired of it;” and she seated herself again on the nest. “Well, how are you getting on?” asked an old duck, who paid her a visit. “One egg is not hatched yet,” said the duck, “it will not break. But just look at all the others, are they not the prettiest little ducklings you ever saw? They are the image of their father, who is so unkind, he never comes to see.” “Let me see the egg that will not break,” said the duck; “I have no doubt it is a turkey's egg. I was persuaded to hatch some once, and after all my care and trouble with the young ones, they were afraid of the water. I quacked and clucked, but all to no purpose. I could not get them to venture in. Let me look at the egg. Yes, that is a turkey's egg; take my advice, leave it where it is and teach the other children to swim.” “I think I will sit on it a little while longer,” said the duck; “as I have sat so long already, a few days will be nothing.” “Please yourself,” said the old duck, and she went away. At last the large egg broke, and a young one crept forth crying, “Peep, peep.” It was very large and ugly. The duck stared at it and exclaimed, “It is very large and not at all like the others. I wonder if it really is a turkey. We shall soon find it out, however when we go to the water. It must go in, if I have to push it myself.” On the next day the weather was delightful, and the sun shone brightly on the green burdock leaves, so the mother duck took her young brood down to the water, and jumped in with a splash. “Quack, quack,” cried she, and one after another the little ducklings jumped in. The water closed over their heads, but they came up again in an instant, and swam about quite prettily with their legs paddling under them as easily as possible, and the ugly duckling was also in the water swimming with them. “Oh,” said the mother, “that is not a turkey; how well he uses his legs, and how upright he holds himself! He is my own child, and he is not so very ugly after all if you look at him properly. Quack, quack! come with me now, I will take you into grand society, and introduce you to the farmyard, but you must keep close to me or you may be trodden upon; and, above all, beware of the cat.” When they reached the farmyard, there was a great disturbance, two families were fighting for an eel's head, which, after all, was carried off by the cat. “See, children, that is the way of the world,” said the mother duck, whetting her beak, for she would have liked the eel's head herself. “Come, now, use your legs, and let me see how well you can behave. You must bow your heads prettily to that old duck yonder; she is the highest born of them all, and has Spanish blood, therefore, she is well off. Don't you see she has a red flag tied to her leg, which is something very grand, and a great honor for a duck; it shows that every one is anxious not to lose her, as she can be recognized both by man and beast. Come, now, don't turn your toes, a well-bred duckling spreads his feet wide apart, just like his father and mother, in this way; now bend your neck, and say ‘quack.’” The ducklings did as they were bid, but the other duck stared, and said, “Look, here comes another brood, as if there were not enough of us already! and what a queer looking object one of them is; we don't want him here,” and then one flew out and bit him in the neck. “Let him alone,” said the mother; “he is not doing any harm.” “Yes, but he is so big and ugly,” said the spiteful duck “and therefore he must be turned out.” “The others are very pretty children,” said the old duck, with the rag on her leg, “all but that one; I wish his mother could improve him a little.” “That is impossible, your grace,” replied the mother; “he is not pretty; but he has a very good disposition, and swims as well or even better than the others. I think he will grow up pretty, and perhaps be smaller; he has remained too long in the egg, and therefore his figure is not properly formed;” and then she stroked his neck and smoothed the feathers, saying, “It is a drake, and therefore not of so much consequence. I think he will grow up strong, and able to take care of himself.” “The other ducklings are graceful enough,” said the old duck. “Now make yourself at home, and if you can find an eel's head, you can bring it to me.” And so they made themselves comfortable; but the poor duckling, who had crept out of his shell last of all, and looked so ugly, was bitten and pushed and made fun of, not only by the ducks, but by all the poultry. “He is too big,” they all said, and the turkey cock, who had been born into the world with spurs, and fancied himself really an emperor, puffed himself out like a vessel in full sail, and flew at the duckling, and became quite red in the head with passion, so that the poor little thing did not know where to go, and was quite miserable because he was so ugly and laughed at by the whole farmyard. So it went on from day to day till it got worse and worse. The poor duckling was driven about by every one; even his brothers and sisters were unkind to him, and would say, “Ah, you ugly creature, I wish the cat would get you,” and his mother said she wished he had never been born. The ducks pecked him, the chickens beat him, and the girl who fed the poultry kicked him with her feet. So at last he ran away, frightening the little birds in the hedge as he flew over the palings. “They are afraid of me because I am ugly,” he said. So he closed his eyes, and flew still farther, until he came out on a large moor, inhabited by wild ducks. Here he remained the whole night, feeling very tired and sorrowful. In the morning, when the wild ducks rose in the air, they stared at their new comrade. “What sort of a duck are you?” they all said, coming round him. He bowed to them, and was as polite as he could be, but he did not reply to their question. “You are exceedingly ugly,” said the wild ducks, “but that will not matter if you do not want to marry one of our family.” Poor thing! he had no thoughts of marriage; all he wanted was permission to lie among the rushes, and drink some of the water on the moor. After he had been on the moor two days, there came two wild geese, or rather goslings, for they had not been out of the egg long, and were very saucy. “Listen, friend,” said one of them to the duckling, “you are so ugly, that we like you very well. Will you go with us, and become a bird of passage? Not far from here is another moor, in which there are some pretty wild geese, all unmarried. It is a chance for you to get a wife; you may be lucky, ugly as you are.” “Pop, pop,” sounded in the air, and the two wild geese fell dead among the rushes, and the water was tinged with blood. “Pop, pop,” echoed far and wide in the distance, and whole flocks of wild geese rose up from the rushes. The sound continued from every direction, for the sportsmen surrounded the moor, and some were even seated on branches of trees, overlooking the rushes. The blue smoke from the guns rose like clouds over the dark trees, and as it floated away across the water, a number of sporting dogs bounded in among the rushes, which bent beneath them wherever they went. How they terrified the poor duckling! He turned away his head to hide it under his wing, and at the same moment a large terrible dog passed quite near him. His jaws were open, his tongue hung from his mouth, and his eyes glared fearfully. He thrust his nose close to the duckling, showing his sharp teeth, and then, “splash, splash,” he went into the water without touching him, “Oh,” sighed the duckling, “how thankful I am for being so ugly; even a dog will not bite me.” And so he lay quite still, while the shot rattled through the rushes, and gun after gun was fired over him. It was late in the day before all became quiet, but even then the poor young thing did not dare to move. He waited quietly for several hours, and then, after looking carefully around him, hastened away from the moor as fast as he could. He ran over field and meadow till a storm arose, and he could hardly struggle against it. Towards evening, he reached a poor little cottage that seemed ready to fall, and only remained standing because it could not decide on which side to fall first. The storm continued so violent, that the duckling could go no farther; he sat down by the cottage, and then he noticed that the door was not quite closed in consequence of one of the hinges having given way. There was therefore a narrow opening near the bottom large enough for him to slip through, which he did very quietly, and got a shelter for the night. |

En la kamparo estis

belege! Estis somero. La greno estis flava, la aveno

estis verda. La fojno sur la verdaj herbejoj staris en

fojnamasoj, kaj la cikonio promenadis sur siaj longaj rughaj

piedoj kaj klakadis Egipte, char tiun lingvon ghi

lernis de sia patrino. Chirkau la grenkampo kaj la

herbejoj etendighis grandaj arbaroj, kaj meze de chi

tiuj trovighis profundaj lagoj. Ho, estis belege tie en

la kamparo! En la lumo de la suno kushis malnova

kavalira bieno, chirkauita de profundaj kanaloj, kaj de

la muroj ghis la akvo tie kreskis grandaj folioj de

lapo, kiuj estis tiel altaj, ke sub la plej grandaj tute

rekte povis stari malgrandaj infanoj. Tie estis tiel

sovaghe, kiel en plej profunda arbaro. Tie kushis

anasino sur sia nesto, por elkovi siajn idojn; sed nun

tio preskau tedis al shi, char ghi dauris ja tro

longe, kaj oni shin nur malofte vizitis. La aliaj anasoj

preferis naghadi en la kanaloj, anstatau viziti shin

kaj sidi sub folio de lapo, por babili kun shi. Fine krevis unu ovo post la alia. “Pip, pip!” oni audis, chiuj ovoflavoj vivighis kaj elshovis la kapon. “Rap, rap! Rapidu, rapidu!” shi kriis, kaj tiam ili ekmovighis kaj rapidis lauforte kaj rigardis sub la verdaj folioj chiuflanken. La patrino permesis al ili rigardi, kiom ili volis, char la verda koloro estas bona por la okuloj. “Kiel granda estas la mondo!” diris chiuj idoj; char kompreneble ili nun havis multe pli da loko ol tiam, kiam ili kushis ankorau interne en la ovo. “Chu vi pensas, ke tio estas jam la tuta mondo?” diris la patrino. “La mondo etendighas ankorau malproksime trans la dua flanko de la ghardeno, ghis la kampo de la pastro; tamen tie mi ankorau neniam estis! Vi estas ja chi tie chiuj kune!” shi diris plue kaj levighis. “Ne, mi ne havas, ankorau chiujn! La plej granda ovo chiam ankorau tie kushas! Kiel longe do tio ankorau dauros? Nun tio efektive baldau tedos al mi!” Kaj shi denove kushighis. “Nu, kiel la afero iras?” demandis unu maljuna anasino, kiu venis shin viziti. “Kun tiu unu ovo la afero dauras tiel longe!” diris la kovanta anasino. “Ankorau nenia truo en ghi montrighas. Sed rigardu la aliajn! Ili estas la plej belaj anasidoj, kiujn mi iam vidis. Ili chiuj estas frapante similaj al sia patro. La sentaugulo, li ech ne vizitas min!” “Montru, mi petas, al mi la ovon, kiu ne volas krevi,” diris la maljuna anasino. “Kredu al mi, tio estas ovo de meleagrino! Tiel mi ankau iam estis trompita, kaj mi havis multe da klopodoj kun la idoj, char ili timas la akvon, mi diras al vi. Antaue mi neniel povis elirigi ilin, kiom ajn mi klopodis kaj penis, admonis kaj helpis! Montru al mi la ovon! Jes, ghi estas ovo de meleagrino! Lasu ghin kushi, kaj prefere instruu viajn aliajn infanojn naghi!” “Mi tamen ankorau iom kushos sur ghi!” respondis la anasino. “Se mi jam tiel longe kushis, ne estas ja grave kushi ankorau iom pli!” “Chiu lau sia gusto!” diris la maljuna anasino kaj diris adiau. Fine la granda ovo krevis. “Pip, pip!” diris la ido kaj elrampis. Ghi estis tre granda kaj rimarkinde malbela. La anasino chirkaurigardis ghin. “Tio estas ja terure granda anasido!” shi diris. “Neniu el la aliaj tiel aspektas. Chu efektive tio estas meleagrido? Nu, pri tio ni baldau konvinkighos! Ghi iru en la akvon, ech se mi mem devus ghin tien enpushi!” En la sekvanta tago estis belega vetero. La suno varmege lumis sur chiuj verdaj lapoj. La anasino-patrino, venis kun sia tuta familio al la kanalo. “Plau!” shi ensaltis en la akvon. “Rap, rap!” shi kriis, kaj unu anasido post la alia mallerte ensaltis. La akvo ekkovris al ili la kapon, sed ili tuj suprenighis returne kaj eknaghis fiere, la piedoj movighadis per si mem, kaj chiuj ili sentis sin bone en la malseka elemento, ech la malbela griza ido ankau naghis kune. “Ne, tio ne estas meleagrido!” shi diris. “Oni nur rigardu, kiel bele ghi uzas siajn piedojn, kiel rekte ghi sin tenas! Ghi estas mia propra infano. En efektiveco ghi estas tute beleta, kiam oni ghin nur rigardas pli atente. Rap, rap! Venu kun mi, nun vi ekkonos la mondon. Mi prezentos vin en anasejo, sed tenu vin chiam proksime de mi, por ke neniu tretu sur vin, kaj gardu vin kontrau la kato!” Kaj tiel ili eniris en la anasejon. Terura bruo tie regis; char du familioj batalis inter si pro kapo de angilo, kaj, malgrau tio ghin ricevis la kato. “Vidu, tiel la aferoj iras en la mondo!” diris la anasino-patrino, farinte kaptan movon per la busho, char shi ankau volis havi la kapon de la angilo. “Uzu nur viajn piedojn,” shi diris, “rigardu, ke vi iom rapidu, kaj klinu la kolon antau la maljuna anasino tie. Shi estas chi tie la plej eminenta el chiuj. Hispana sango rulas en shiaj vejnoj, tial shi estas tiel pezeca. Kiel vi vidas, shi portas rughan chifonon chirkau la piedo. Tio estas io nekompareble bela kaj la plej alta distingo, kiun iam ricevis ia anaso. Ghi signifas, ke oni ne volas shin perdi kaj ke shi devas esti rekonebla por bestoj kaj homoj. Movighu! Rapidu! Ne turnu la piedojn internen! Bone edukita anasido larghe disstarigas la piedojn, kiel la patro kaj la patrino! Vidu, tiel! Nun klinu vian kolon kaj diru: ‘Rap!’” Kaj ili tion faris. Sed la aliaj anasoj chirkaue rigardis ilin kaj diris: “Vidu! Nun ni devas ricevi ankorau tiun familiachon, kvazau nia nombro ne estus ankorau sufiche granda! Fi, kiel unu el la anasidoj aspektas! Tion ni ne toleros inter ni!” Kaj tuj unu anaso alflugis kaj mordis la anasidon en la nuko. “Lasu gin trankvila!” diris la patrino, “ghi ja al neniu ion faras!” “Jes, sed ghi estas tiel granda kaj stranga!” diris la anaso, kiu ghin mordis, “kaj tial oni devas gin forpeli!” “Vi havas belajn infanojn, patrineto,” diris kun protekta tono la maljuna anasino kun la chifono chirkau la piedo. “Chiuj ili estas belaj, esceptinte unu, kiu ne naskighis bonforme! Estus bone, se vi povus ghin rekovi!” “Tio ne estas ebla, via moshto!” diris la anasino-patrino. “Ghi ne estas bela, sed ghi havas tre bonan koron, kaj ghi naghas tiel same bone, kiel chiu el la aliaj, mi povas ech diri, ke eble ech iom pli bone. Mi pensas, ke per la kreskado ghi ordighos au kun la tempo ghi farighos iom malpli granda. Ghi kushis tro longe en la ovo, kaj pro tio ghi ne ricevis la gustan formon.” Che tio ghi pinchis la anasidon en la nuko kaj komencis ghin glatigi. “Krom tio,” shi diris plue, “ghi estas virseksulo, kaj la malbeleco sekve ne tiom multe malutilas. Mi esperas, ke ghi ricevos solidan forton, kaj tiam ghi jam trabatos sin en la mondo.” “La ceteraj anasidoj estas ja tute beletaj!” diris la maljunulino. “Sentu vin tute kiel hejme, kaj se vi trovos kapon de angilo, vi povas ghin alporti al mi.” Kaj ili sentis sin kiel hejme. Sed la kompatinda anasido, kiu elrampis el la ovo la lasta kaj estis tiel malbela, estis mordata, pushata kaj persekutata kiel de la anasoj, tiel ankau de la kokinoj. “Ghi estas tro granda,” ili chiuj diris, kaj la meleagro, kiu naskighis kun spronoj kaj tial imagis al si, ke li estas regho, plenblovis sin kiel shipo kun etenditaj veloj, iris rekte al la anasido, kriis rulrule, kaj lia kapo farighis tute rugha. La kompatinda anasido ne sciis, kiel ghi devas stari, nek kiel ghi devas iri. Ghi estis malghoja, ke ghi aspektas tiel malbele kaj estas objekto de mokado por la tuta anasejo. Tiel estis en la unua tago, kaj poste farighis chiam pli kaj pli malbone. La malfelicha anasido estis pelata de chiuj, ech ghiaj gefratoj estis tre malbonkondutaj kontrau ghi kaj chiam diradis: “Ho, se la kato volus vin kapti, vi malbela estajho!” Kaj la patrino ghemadis: “Ho, se vi estus malproksime de chi tie!” La anasoj ghin mordadis, la kokinoj ghin bekadis, kaj la servistino kiu alportadis mangajhon, pushadis ghin per la piedo. Tial ghi forkuris kaj flugis trans la barilon. La birdetoj en la arbetajhoj timigite levighis en la aeron! “Pri tio mia malbeleco estas kulpa!” pensis la anasido kaj fermis la okulojn, kurante tamen pluen. Tiamaniere ghi venis ghis la granda marcho, en kiu loghas la sovaghaj anasoj. Tie ghi kusis dum la tuta nokto, char ghi estis tre laca kaj malghoja. Matene la sovaghaj anasoj levighis kaj ekvidis la novan kamaradon. “El kie vi estas?” ili demandas, kaj la anasido sin turnis chiuflanken kaj salutis, kiel ghi nur povis. “Vi estas terure malbela!” diris la sovaghaj anasoj, “sed tio estas por ni indiferenta, se vi nur ne enedzighos en nian familion!” La kompatinda anasido certe tute ne pensis pri edzigho. Por ghi estis grave nur ricevi la permeson kushi en la kanaro kaj trinki akvon el la marcho. Dum tutaj du tagoj ghi tie kushis. Tiam tien venis du sovaghaj anseroj. Ili ankorau antau nelonge elrampis el la ovo, kaj tial ili estis iom malmodestaj. “Auskultu, kamarado, vi estas tiel malbela, ke vi havas specialan belecon kaj plachas al ni. Chu vi volas alighi al ni kaj esti migranta birdo? Tute apude en alia marcho loghas kelkaj dolchaj, charmaj sovaghaj anserinetoj, fraulinoj, kiuj povoscias charmege babili ‘Rap, rap’; vi povas aranghi al vi felichon, kiel ajn malbela vi estas!” “Pif, paf!” eksonis subite krakoj, kaj ambau sovaghaj anseroj falis senvive en la kanaron, kaj la akvo farighis rugha de sango. “Pif, paf!” denove eksonis krakoj, kaj tutaj amasoj da sovaghaj anseroj ekflugis supren el la kanaro, kaj poste denove audighis krakoj. Estis granda chasado; la chasistoj kushis chirkau la marcho, kelkaj ech sidis supre en la arbobranchoj, kiuj etendighis malproksimen super la kanaron. La blua fumo de pulvo tirighis kiel nuboj tra inter la mallumaj arboj kaj flugpendis super la akvo. En la marchon enkuris la chas-hundoj. Plau, plau! La kanoj klinighis chiuflanken. Kia teruro tio estis por la kompatinda anasido! Ghi turnis la kapon, por shovi ghin sub la flugilojn; sed en la sama momento tute antau ghi aperis terure granda hundo; la lango de la besto estis longe elshovita el la gorgho, kaj ghiaj okuloj brilis terure. Ghi preskau ektushis la anasidon per sia bushego, montris la akrajn dentojn kaj... plau! ghi retirighis, ne kaptinte ghin. “Danko al Dio!” ghemis la anasido, “mi estas tiel malbela, ke ech la hundo ne volas min mordi!” Tiel ghi kushis tute silente, dum en la kanaro zumis la kugletajho kaj krakis pafo post pafo. Nur malfrue posttagmeze farighis silente, sed la kompatinda anasido ankorau ne kuraghis sin levi. Ghi atendis ankorau kelke da horoj, antau ol ghi ekrigardis chirkauen, kaj tiam ghi elkuris el la marcho tiel rapide, kiel ghi nur povis. Ghi kuris trans kampojn kaj herbejojn, sed estis tia ventego, ke ghi nur malfacile povis movighi antauen. Chirkau la vespero ghi atingis mizeran vilaghan dometon, kiu estis en tia kaduka stato, ke ghi mem ne sciis, sur kiun flankon ghi falu, kaj tial ghi restis starante. La ventego tiel bruis chirkau la malfelicha anaseto, ke ghi devis sidighi, por sin teni. Kaj farighis chiam pli kaj pli malbone. Tiam ghi rimarkis, ke la pordo delevighis de unu hoko kaj pendis tiel malrekte, ke tra la fendo oni povis trashovighi en la chambron; kaj tion ghi faris. |

Хорошо было за городом! Стояло лето. На полях уже золотилась рожь, овес зеленел, сено было смётано в стога; по зеленому лугу расхаживал длинноногий аист и болтал по-египетски - этому языку он выучился у своей матери. За полями и лугами темнел большой лес, а в лесу прятались глубокие синие озера. Да, хорошо было за городом! Солнце освещало старую усадьбу, окруженную глубокими канавами с водой. Вся земля - от стен дома до самой воды - заросла лопухом, да таким высоким, что маленькие дети могли стоять под самыми крупными его листьями во весь рост.

В чаще лопуха было так же глухо и дико, как в густом лесу, и вот там-то сидела на яйцах утка. Сидела она уже давно, и ей это занятие порядком надоело. К тому же ее редко навещали, - другим уткам больше нравилось плавать по канавкам, чем сидеть в лопухе да крякать вместе с нею.

Наконец яичные скорлупки затрещали.

Утята зашевелились, застучали клювами и высунули головки.

- Пип, пип! - сказали они.

- Кряк, кряк! - ответила утка. - Поторапливайтесь!

Утята выкарабкались кое-как из скорлупы и стали озираться кругом, разглядывая зеленые листья лопуха. Мать не мешала им - зеленый цвет полезен для глаз.

- Ах, как велик мир! - сказали утята. Еще бы! Теперь им было куда просторнее, чем в скорлупе.

- Уж не думаете ли вы, что тут и весь мир? - сказала мать. - Какое там! Он тянется далеко-далеко, туда, за сад, за поле... Но, по правде говоря, там я отроду не бывала!.. Ну что, все уже выбрались? - Иона поднялась на ноги. - Ах нет, еще не все... Самое большое яйцо целехонько! Да когда же этому будет конец! Я скоро совсем потеряю терпение.

И она уселась опять.

- Ну, как дела? - спросила старая утка, просунув голову в чащу лопуха.

- Да вот, с одним яйцом никак не могу справиться, - сказала молодая утка. - Сижу, сижу, а оно всё не лопается. Зато посмотри на тех малюток, что уже вылупились. Просто прелесть! Все, как один, - в отца! А он-то, негодный, даже не навестил меня ни разу!

- Постой, покажи-ка мне сперва то яйцо, которое не лопается, - сказала старая утка. - Уж не индюшечье ли оно, чего доброго? Ну да, конечно!.. Вот точно так же и меня однажды провели. А сколько хлопот было у меня потом с этими индюшатами! Ты не поверишь: они до того боятся воды, что их и не загонишь в канаву. Уж я и шипела, и крякала, и просто толкала их в воду, - не идут, да и только. Дай-ка я еще раз взгляну. Ну, так и есть! Индюшечье! Брось-ка его да ступай учи своих деток плавать!

- Нет, я, пожалуй, посижу, - сказала молодая утка. - Уж столько терпела, что можно еще немного потерпеть.

- Ну и сиди! - сказала старая утка и ушла. И вот наконец большое яйцо треснуло.

- Пип! Пип! - пропищал птенец и вывалился из скорлупы.

Но какой же он был большой и гадкий! Утка оглядела его со всех сторон и всплеснула крыльями.

- Ужасный урод! - сказала она. - И совсем не похож на других! Уж не индюшонок ли это в самом деле? Ну, да в воде-то он у меня побывает, хоть бы мне пришлось столкнуть его туда силой!

На другой день погода стояла чудесная, зеленый лопух был залит солнцем.

Утка со всей своей семьей отправилась к канаве. Бултых! - и она очутилась в воде.

- Кряк-кряк! За мной! Живо! - позвала она, и утята один за другим тоже бултыхнулись в воду.

Сначала вода покрыла их с головой, но они сейчас же вынырнули и отлично поплыли вперед. Лапки у них так и заработали, так и заработали. Даже гадкий серый утёнок не отставал от других.

- Какой же это индюшонок? - сказала утка. - Вон как славно гребет лапками! И как прямо держится! Нет, это мой собственный сын. Да он вовсе не так дурен, если хорошенько присмотреться к нему. Ну, .живо, живо за мной! Я сейчас введу вас в общество - мы отправимся на птичий двор. Только держитесь ко мне поближе, чтобы кто-нибудь не наступил на вас, да берегитесь кошек!

Скоро утка со всем своим выводком добралась до птичьего двора. Бог ты мой! Что тут был за шум! Два утиных семейства дрались из-за головки угря. И в конце концов эта головка досталась кошке.

- Вот так всегда и бывает в жизни! - сказала утка и облизнула язычком клюв - она и сама была не прочь отведать угриной головки. - Ну, ну, шевелите лапками! - скомандовала она, поворачиваясь к утятам. - Крякните и поклонитесь вон той старой утке! Она здесь знатнее всех. Она испанской породы и потому такая жирная. Видите, у нее на лапке красный лоскуток! До чего красиво! Это высшее отличие, какого только может удостоиться утка. Это значит, что ее не хотят потерять, - по этому лоскутку ее сразу узнают и люди и животные. Ну, живо! Да не держите лапки вместе! Благовоспитанный утенок должен выворачивать лапки наружу. Вот так! Смотрите. Теперь наклоните головки и скажите: “Кряк!”

Утята так и сделали.

Но другие утки оглядели их и громко заговорили:

- Ну вот, еще целая орава! Точно без них нас мало было! А один-то какой гадкий! Этого уж мы никак не потерпим!

И сейчас же одна утка подлетела и клюнула его в шею.

- Оставьте его! - сказала утка-мать. - Ведь он вам ничего не сделал!

- Положим, что так. Но какой-то он большой и несуразный! - прошипела злая утка. - Не мешает его немного проучить.

А знатная утка с красным лоскутком на лапке сказала:

- Славные у тебя детки! Все очень, очень милы, кроме одного, пожалуй... Бедняга не удался! Хорошо бы его переделать.

- Это никак невозможно, ваша милость! - ответила утка-мать. - Он некрасив - это правда, но у него доброе сердце. А плавает он не хуже, смею даже сказать - лучше других. Я думаю, со временем он выровняется и станет поменьше. Он слишком долго пролежал в яйце и потому немного перерос. - И она разгладила клювом перышки на его спине. - Кроме того, он селезень, а селезню красота не так уж нужна. Я думаю, он вырастет сильным и пробьет себе дорогу в жизнь.

- Остальные утята очень, очень милы! - сказала знатная утка. - Ну, будьте как дома, а если найдете угриную головку, можете принести ее мне.

И вот утята стали вести себя как дома. Только бедному утенку, который вылупился позже других и был такой гадкий, никто не давал проходу. Его клевали, толкали и дразнили не только утки, но даже куры.

- Слишком велик! - говорили они.

А индийский петух, который родился со шпорами на ногах и потому воображал себя чуть не императором, надулся и, словно корабль на всех парусах, подлетел прямо к утенку, поглядел на него и сердито залопотал; гребешок у него так и налился кровью. Бедный утенок просто не знал, что ему делать, куда деваться. И надо же было ему уродиться таким гадким, что весь птичий двор смеется над ним!

Так прошел первый день, а потом стало еще хуже. Все гнали бедного утенка, даже братья и сестры сердито говорили ему: “Хоть бы кошка утащила тебя, несносный урод!” А мать прибавляла: “Глаза б мои на тебя не глядели!” Утки щипали его, куры клевали, а девушка, которая давала птицам корм, отталкивала его ногою.

Наконец утенок не выдержал. Он перебежал через двор и, распустив свои неуклюжие крылышки, кое-как перевалился через забор прямо в колючие кусты.

Маленькие птички, сидевшие на ветках, разом вспорхнули и разлетелись в разные стороны.

"Это оттого, что я такой гадкий", - подумал утенок и, зажмурив глаза, бросился бежать, сам не зная куда. Он бежал до тех пор. пока не очутился в болоте, где жили дикие утки.

Тут он провел всю ночь. Бедный утенок устал, и ему было очень грустно.

Утром дикие утки проснулись в своих гнездах и увидали нового товарища.

- Это что за птица? - спросили они. Утенок вертелся и кланялся во все стороны, как умел.

- Ну и гадкий же ты! - сказали дикие утки. - Впрочем, нам до этого нет никакого дела, только бы ты не лез к нам в родню.

Бедняжка! Где уж ему было и думать об этом! Лишь бы ему позволили жить в камышах да пить болотную воду, - о большем он и не мечтал.

Так просидел он в болоте два дня. На третий день туда прилетели два диких гусака. Они совсем недавно научились летать и поэтому очень важничали.

- Слушай, дружище! - сказали они. - Ты такой чудной, что на тебя смотреть весело. Хочешь дружить с нами? Мы птицы вольные - куда хотим, туда и летим. Здесь поблизости есть еще болото, там живут премиленькие дикие гусыни-барышни. Они умеют говорить: "Рап! Рап!" Ты так забавен, что, чего доброго, будешь иметь у них большой успех.

Пиф! Паф! - раздалось вдруг над болотом, и оба гусака упали в камыши мертвыми, а вода покраснела от крови.

Пиф! Паф! - раздалось опять, и целая стая диких гусей поднялась над болотом. Выстрел гремел за выстрелом. Охотники окружили болото со всех сторон; некоторые из них забрались на деревья и вели стрельбу сверху. Голубой дым облаками окутывал вершины деревьев и стлался над водой. По болоту рыскали охотничьи собаки. Только и слышно было: шлёп-шлёп! И камыш раскачивался из стороны в сторону. Бедный утенок от страха был ни жив ни мертв. Он хотел было спрятать голову под крылышко, как вдруг прямо перед ним выросла охотничья собака с высунутым языком и сверкающими злыми глазами. Она посмотрела на утенка, оскалила острые зубы и - шлёп-шлёп! - побежала дальше.

"Кажется, пронесло, - подумал утенок и перевел дух. - Видно, я такой гадкий, что даже собаке противно съесть меня!"

И он притаился в камышах. А над головою его то и дело свистела дробь, раздавались выстрелы.

Пальба стихла только к вечеру, но утенок долго еще боялся пошевельнуться.

Прошло несколько часов. Наконец он осмелился встать, осторожно огляделся вокруг и пустился бежать дальше по полям и лугам.

Дул такой сильный встречный ветер, что утенок еле-еле передвигал лапками.

К ночи он добрался до маленькой убогой избушки. Избушка до того обветшала, что готова была упасть, да не знала, на какой бок, потому и держалась.

Ветер так и подхватывал утенка, - приходилось прижиматься к самой земле, чтобы не унесло.

К счастью, он заметил, что дверь избушки соскочила с одной петли и так перекосилась, что сквозь щель можно легко пробраться внутрь. И утенок пробрался.