|

• Çäåñü — Ðàçáîðêà ãðóçîâèêîâ: Ìàí, Ìåðñåäåñ, Âîëüâî, Èâåêî, Ðåíî, Ñêàíèÿ, Äàô (lideravto.ru) • Ñòóäèè àâòîïîðòðåòà — Çàïèøèòåñü íà ôîòîñåññèþ â ëó÷øèõ ñòóäèÿõ Ìîñêâû (phot.studio) |

STRANGLED CRIES

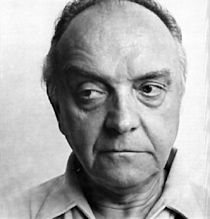

A profile of poet Julius Balbin

The apartment of Doctor Julius Balbin on the Upper West

Side of Manhattan is filled with books.

Looking at their titles, one can comprehend the

life of poet Julius Balbin, year after year.

Julian, Tuvim and Boleslaw Prust in Polish (Julius' native

tongue); Shalom Aleichem in Yiddish (his mother's tongue); poetry

and novels in Russian, French, German, Italian and Spanish, and

books in Esperanto - the international language invented by a

Polish Jew, Doctor Lazar Zamenhof.

Of all the languages, Esperanto is especially close to

Julius' heart, and though he's fluent in many languages (he's

Professor of English at Essex Community College in Newark, New

Jersey), Julius speaks from his heart in Esperanto. When I ask

him why he chooses Esperanto above all other languages in the

world, he answers, reciting from one of his poem from his book, Strangled

Cries:

"Why do I write poems in Esperanto...

A language wrought by a man, empty of world

prestige,

Which conquered neither a land nor a people?

I do persist in expressing in this language

The song of my heartbeat.

For even if the edge

Of its sword is not sharp enough to rule the

world

It is incomparable as the medium: euphonious,

Designed by a genius, and so flexible as to

open

And perhaps conquer human hearts."

Julius Balbin strongly

believes in the poetic power of Esperanto. This poem, along with

many others, was published in 1981 as a chapbook by

Cross-Cultural Communications, Merrick, New York. The original

Esperanto text is accompanied by an English translation by Charlz

Rizutto of New York City.

Charlz and Julius became friends, united by their comon

passion which cannot be divided even by the frontiers of

language. Strangled Cries is one of a series of

chapbooks featuring bilingual texts.

In a recent interview in his Manhattan apartment, Julius

Balbin, survivor of four concentration camps, three in Poland and

one in Austria, speaks out about art, love, passion and the

instinct ti survive. Balbin survived Mauthausen, Plaszow,

Wieliczka and Linz.

"I am fond of New York City", he says, looking

out of his West End Avenue window, "and do you know why?

Because it does not belong to any one ethnic group or

nationality. There are so many people from so many different

lands in Manhattan that it reminds me of a new Noah's arc sent by

humankind into the future."

"I don't know

why," he says "that Henry Hudson thought he was

mistaken when he found the Hudson River - thought he was so far

from India and Japan, which he was looking for - because in my

mind, this broad river runs through time and begins someplace

near my native Cracow, in Poland."

Julius always returns to his youth, to his Poland where

"even the stones speak Yiddish." Poland where almost

all the Jews were exterminated by the Nazis and the rest were

forced to leave.

In his early years Julius lived under the spell of

linguist and Jewish thinker Lazar Zamenhof (1859-1917) who

finally gave up the Zionist idea (he was one of the first

Zionists in Poland) for a utopian dream - the idea of Esperanto,

a language that would transform all the peoples of the world into

one big family.

Nobody could believe that the Holocaust was looming on the

horizon.

When Adolf Hitler took over, Julius was a student at the

Jagellonian University of Cracow where he had taken up many

courses in English and Romance languages. Esperanto was the voice

of his heart, though, and he'd been writing poetry since the age

of fourteen.

In 1937, in Warsaw, the native city where Zamenhof

published his first book on (and in) Esperanto in 1887, the

Esperanto Congress was convened. During the same time, Hitler

blamed the language as "the creation of Jews who sought to

rule the world, forcing the world to speak one language, invented

by a Jew," Stalin coined a name for Esperanto - "the

language of the spies and Zionists."

During 1937-1947, thousands of Esperantists, in the Europe

of Hitler and in the USSR under Stalin, perished in concentration

camps.

"And were these mostly Jews?" I ask him.

"Yes," he answers, "but only some. Two

dictators, each waging war against the other, were unanimous in

their hate of the 'Jewish idea of Zamenhof.' Hitler's Gestapo,

invading the Baltic Republics occupied by the Soviets, used the

lists left by the KGB and used these lists to persecute

Esperantists."

"But why," Balbin says, "are we speaking so

much about the Esperantists? There were just thousands of them.

Can you compare this with 6 millions Jews? But the answer is that

that you can, and it is because we Jews are humanistic.

We believe in the value of any human life."

"For me," he says, "the death of Zamenhof's

family and Janusz Korczak in Hitler's camps means more than

hundreds of tombs of unknown people.

"As a poet," he says, "I see faces and look

into their minds..."

On Julius' arm is the number 88834. I recite his poem and

I finally comprehend why he so hates numbers.

"Long before the invention of the

computer

I was a mere number

tattoed upon my arm

and humanity's conscience.

It is possible the latter in science,

and technology's unimpeded and triumphant

progress,

will eventually be disinvented."

Many years ago, he, a man with a number and a personality

was lowered to the level of unnamed beast, to a mere number. It

all began in Poland where Jews were viewed as "dirty

kikes" and where mocking cartoons and derogatory songs about

Jews, beatings and pogroms prepared Poland to adopt on its own

soil most of the concentration camps.

"If you really want to be accurate," he says,

"I was not really born in Poland. In 1917 my native Cracow

belonged to Austria-Hungary."

"Interesting," Balbin says, "that both

Hitler and I were born in the same country. We were

compatriots."

"During the First World War," he says, "my

father was a captain in the Austrian army. He met the Nazis

decorated with all of his orders, in his officer's uniform. He

was even more dazzling than was the father of my girlfriend,

Hanna Bahner, who was the well-known president of the Union of

Jews-Combatants."

"What can I tell you?" Balbin asks. "When

God is to punish somebody he first deprives them of his mind. Now

for the Nazis, as before for Polish anti-Semites, we were just

'kikes'."

"Two months after Hitler invaded Poland, all the Jews

were ordered to wear the Yellow Star. After that we were driven

out of the Cracow Ghetto and sent to concentration camps, most of

us were sent to the infamous Auschwitz."

Suddenly Julis falls into silence. After World War II, the

survivors were so astounded by their bitter experiences, by the

terrible abyss where human conscience could fall, that they kept

their mouths sealed. Only many years after events, they realized:

people must remember the Holocaust if they do not want it to be

repeated.

What does he see out of his window? May by not New York

City but Mauthausen, his second camp. He often lives in the past.

"Sinking striped rags

hang from cavernous bodies

cursed by birth or chance

while they cry in silence

smothered by the sniggering sun..."

The rest oft the world knows it was a living hell, but it

lives somewhere outside his memory, remote like the moon. Poet

Julius Balbin is pregnant with the hell. He speaks out for the

dead, who are buried in his mind.

"Tonight the silence of my room

weighs on my chest.

As I shudder, the silence of my room

enshrouded tortured millions

the womb of the aborted world.

The silence of my room

is the coffin of my martyred mother."

Her name was Beila (Balbina - in Polish), and Julius loved

his mother more than anybody else in the world. But what can be

compared with the love for one's mother?

It happened in the fall of 1942. The radio announced that

the Jews of the Cracow Ghetto had to be ready for exportation.

The night before, Julius was sitting in the basement, embracing

his mother. They went out onto the street, grasping each other,

but the whips of policemen separated them. All of the Jews got

into two columns. One of the two wolud be marching to the gas

chamber. No one knew which column that would be. Julius wanted

his mother to outlive him. But fate made another decision.

Approaching the gas chamber, Beila realized that her

column was the one going "on gas". She smiled and waved

her hand. Julius was not able to hear her mother's voice but he

understood - she had given him her blessing.

"Did you want to share her destiny?" I ask

Balbin.

"Only the first days after her death," he says.

"I knew that after I died, the memory of her would vanish

from this world. I had an ardent desire to survive. I changed my

name to Balbin - for my mother Beila to be remembered."

One night I slept in Julius' apartment. When I was about

to turn of the lights, he told me, "Leave some light for my

mother." There was a screen with a sculpted portrayal of

Beila by his bed. A small lamp illuminates it day and night.

"Do not ask me,"he says, "how I survived. I

had a lot of luck, as if it had been given to me by my mother. I

was not a kind of hero, no. But I never bertayed my friends. I

fell in love and the passion enabled me to live."

A love in the concentration camp: was it possible?

The silence of my room

is pregnant with the sound

Of your voice

that rings with the screams

of the day we parted.

Her name was Hanna Bachner. Two youngsters, Julius and

Hanna, were fond of each other. But in the camp they lived

divided by the wire. He in the male part, she in the female part.

Julius worked as an aide to the dentist (this dentist was

his father) and was given extra food. When night fell, Julius

would jump over the wire fence under the guards' bullets to his

fiancee, with some bread in his hands. They ate and made love,

knowing that each of these encounters could be the last. But they

were ready to pay with their lives for those heavenly moments.

Hanna was shot to death by a Nazi, together with her

mother. From that day on, two more people were buried in Julius'

heart. Julius has been faithful to his fiancee until even now -

he had never been married.

"They call us survivors," he says. "It is

true about me. I sought to survive. I was not a hero."

"Do you remember any heroes in the concentration

camps?" I ask him.

"Some of them," he responds. "I remember

how two Russian Jews escaped. They were caught and executed in

the presence of all of us inmates. In their last moment, they

shouted: "We will overcome! Long live our fatherland!"

"What did you do in the camp? What did you daily

tasks consist of?" I ask him, the former inmate of four

camps.

"We robbed a Jewish cemetery," he answers.

"Yes, the German knew how to humiliate us. We dug out the

gravestones to build slum houses for the inmates. That way we

robbed the deceased to help the living corpses." He laughs.

"However, every day more and more of us joined the

dead."

"Every morning," he continues, "on the

'appelplatz' (the call-over place), a wolf in human appearance,

German officer Amon Gott, would shoot to death ten of us at

random, just for fun." He pauses and looks out of the

window... "Don't ask me," he says, "why I got a

happy lot."

Balbin was luckier than most, though. His last camp was

not in Poland but in Austria. If he would have lived to be set

free by the Soviets, he could have been sent to Siberia (as many

of the Jews were. The KGB acused the survivors of collaborating

with the Nazis to keep alive.)

On May 5. 1945, the camp in Linz was liberated by the

American Army. After the Americans saw what was done to the

prisoners they asked, "What do you want first?" And

the answer came. "To avenge ourselves on our

torturers."

And they were given handguns and knives.

At that time, Julius was a living corpse. For many months,

he recovered in an American hospital. After the Communists took

over in Poland, he realized that this country was not good at all

for Jews and he tried to go to America. But emigration there was

restricted.

Life for ex-patriots has never been easy. For survivors,

though, it's immensely harder. He lived in Austria where German

is spoken and felt like a ghost among the living. He felt as

though he was in an even larger concentration camp.

In 1951, Balbin was granted an American entrance visa. He

came to New York City on board a navy boat. There was a storm on

the sea and the city looked like a huge ship waiting for its

lifeboat. Among the rescued, from the Old World, was Professor

Julius Balbin.

He had gotten his Ph.d. from Vienna University and was

eager to teach English in America.

"The metropolitan area," he comments, "is a

real Babylon. There is a real need for one common language so the

people will not be as confused as the builders of the

Babylon tower were. In America, it is English, but to the

world, it is Zamenhof's Esperanto."

Julius Balbin, Professor of English at Essex College in

Newark, New Jersey, is a sciencist and a dreamer. For four years

he served as a president of the New York Esperanto Society,

lectured on the topic - the one language for the world in the

U.N. - and visited many Esperantists' meetings abroad.

However, his life has never been easy.

He reminds me one of the heroes of Saul Bellow novels.

Like Mr. Sammler, survivor, of the novel Mr.Sammler's Planet, he

hates the subway. With its darkness and dim lights, the subway

looks like the salt mines of Wieliczka in Poland where Julius

worked in Hitler's time. And the crowded subway cars remind him

of the trains transporting Jews to Auschwitz. Maybe this

is the reason Julius prefers walking everywhere.

"I do not blame the subways," he says, "I

blame the people who are indifferent to whatever it is - graffiti

or crime. These kind of people never care when or where somebody

is killed." "Bruno Yasensky, a Jewish writer who

perished in the Gulag said, "Do not be afraid of your

enemies - they would kill you; do not be scared by the false

friends - they could just betray you; but stay away from people

who do not care: their silent consent approves of all the crime

on earth."

"Rocks fell and tombs opened when

The King of Jews was crowned with thorns

and crusified the martyr

as followers screamed in horror.

But the earth remained calm,

almost indifferent

to six million Jews dying a martyr's death

at the hands of the new Teutons

with deaf and dump mankind,

a silent accomplice."

Julius Balbin does not complain; he accuses humankind of

the Holocaust. He is the poetic voice of "those martyrs

whose sole memories are mournful woes exhaled from the throats of

those saved."

For them to be remembered, Balbin lectured on the

Holocaust at the City University of New York. He translated into

Esperanto Yevtushenko's "Babi Yar" and was awarded an

international prize for the translation.

Every summer he goes to the Esperanto Congress, every year

in another country, where he talks on the Holocaust, and from

there goes around the world. This voyage included his 'haj' to

Israel where his sister lives.

"Israel is our world-be asylum," he says.

"If the country had existed many decades ago, the

catastrophe of the six million would never have happened."

I ask him, "Do you think that something similar could

happen in the future?"

Julius kept silent. "Why do you ask me?" he

says. "Ask yourself. Look: Jews are the high priority target

on every crime list. We are killed every day all around the world

and even in our own Jewish state."

"Listen to the Arab radios or to the debates in the

United Nations," he says, "So many countries would like

to transform Israel into a new concentration camp."

Julius Balbin sits up very straight in his chair, as if

for emphasis. "Mr. Churchill would say 'The only conclusion

that humankind drew from history is that it drew no conclusion at

all.' If he was right, we cannot be optimistic."

"However," Balbin says, "I try to believe

in the future. I cannot imagine that the world is doomed and that

people have no future at all."

By Alexander Kharkovsky

Alexandr Kharkovsky is a journalist living in New Jersey.

| IMPERIO DE L' KOROJ Spite al tiom da homoj ofte demandantaj: "Kial vi verkadas poemojn en Esperanto? En ghi ja nek naskighis ech unu popolkanto, Nek brilas ghi per facetoj diamantaj. Lingvo artefarita, sen ia mondprestigho, Konkerinta neniun landon, neniun genton - kiel do ghi kapablas esprimi sentimenton?" Spite tiujn dubantojn pri ghia kulturigho, daurigas mi persiste eldiri en chi lingvo miajn plej intimajn sentojn. Char ech se la klingo de ghia glav' ne akras sufiche por mondregno, ghi pompas kiel esprimil': belsona, fleksebla, montranta la strukturon de l' genia desegno - do l' homajn korojn konkeri neniel tro febla. |

EMPIRE OF HEARTS In spite of all those asking Why do you write poems in Esperanto? A tongue without the brilliance of an uncut diamond In which not even one folksong was sung. A language wrought by a man, empty of world prestige, Which conquered neither a land nor a people, How could it express a single sentiment?" In spite of all those deaf to its melody I do persist in expressing in this language The song of my heartbeat. For even if the edge Of its sword is not sharp enough to rule the world It is incomparable as the medium: euphonious, Designed by a genius, and so flexible as to open And perhaps conquer human hearts. |